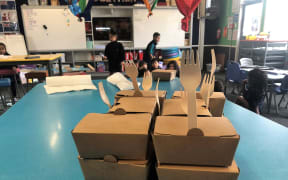

As many as 50 charter schools could be operating by the end of 2026 with funding from taxpayers, the government says, despite criticism of how they were monitored between 2014 and 2018. (File photo) Photo: RNZ / Richard Tindiller

Reintroduced charter schools will be tightly monitored to high standards, the government promises, however, lack of transparency in reporting was a key criticism levelled at previous charter schools.

Associate Education Minister David Seymour says the government's Budget will include $153 million, over four years, for the controversial publicly-funded private schools, but the announcement has been met with mixed reactions from education figures.

As many as 35 state schools could convert to charter status at the start of next year with a further 15 entirely new schools opening in 2026, he said.

Charter schools get bulk funding from the government, operate as not for profit businesses, have wide freedoms that state schools don't have - including over their own curriculum and hours, can use unregistered teachers and would even be exempt from policies like the cellphone ban.

Read more:

- Charter schools - are they better than public schools?

- Watch: Charter schools to get $135m in new funding in budget 2024

Charter schools were originally set up after the 2011 election as part of a confidence and supply agreement between National and Act but were abolished under Labour. This time round their resurrection fulfils a coalition promise to Associate Education Minister David Seymour.

A lot of schools were interested in becoming charters, Seymour said: "They wish to have the kind of flexibility and autonomy over their funding to be able to employ without rigid union contracts, and to be able to chart their own destinies and be able to run their schools their way."

The schools would have 10 year contracts setting out expected standards they must meet for minimum attendance and achievement goals and could be shut down if they did not measure up. That meant a higher level of accountability than state schools, Seymour said.

The schools were very successful when they ran from 2014 to 2018, he said: "There was overwhelming success in the previous charter model".

"The level of reporting was vastly stronger and better than state schools and in actual fact this is a model that leads to greater accountability than any other model of school in New Zealand," he claimed.

But, the Ministry of Education concluded that last time around the monitoring was inadequate and apart from two schools, there was no independent evidence they were doing a better job than comparable state schools - in fact, their results might have been inaccurate or even fabricated.

Teacher unions had opposed the policy.

Post Primary Teachers' Association (PPTA) president Chris Abercrombie said the funds would be better spent in the public school system and the move would divert hundred of millions of much needed dollars from state schools.

"It's taking public money and putting it into private pockets, and making money off children.

"It's the privatisation of a public good. It's for the betterment of the whole nation to have a really strong public education system.

"It takes money out of the state system at a time where the government is counting every dollar, to put hundreds of millions of dollars into a proven failure is not really the best use of public money."

Overseas, there had been examples of public schools suddenly closing, leaving "thousands of children without a school to go to," Abercrombie said.

"We need to improve the state system, it's where the vast majority of students go ... it's where the qualified registered teachers are, we need to improve that system and not divert money away. We don't see the need to create a separate system to achieve that - we improve it."

Seymour's claims that charter schools would suit students not achieving in state schools were odd given schools already had wide freedoms that allowed wide diversity, he said.

"New Zealand already has one of the most devolved systems in the world - so I'm not sure why he's talking about freedom. We've already got a devolved education system that creates freedom, we've got special character, we've got state integrated, we've got religious, we've got sporting schools, we've got all of this freedom already within this system. We don't see the need to create a separate system to achieve that.

"It just seems really interesting that this charter school system is going to be separate from the state system where the government is busy saying we have to have phones away for the day, an hour a day of reading, writing and maths, a knowledge-based curriculum, but this charter system's going to have none of those."

There was a lack of detail about how funding for the schools would work, Abercrombie said: "Is that [$153m] going to be startup costs as well as ongoing costs, is that payroll, is that insurance, is that all of those things? - We just don't know."

Charter schools would not be held to the same requirements for their staff to be qualified teachers, which could help them avoid the recruitment difficulties schools have faced, he said.

Abercrombie said some teachers might choose not to work for charter schools out of principle, but others could feel they had no option due to wider financial pressures, however the union believed those at existing schools that convert to charter schools would be entitled to redundancy payments.

Papatoetoe High School principal Vaughan Couillault said New Zealand schools already had a lot of independence and he was not convinced another type of school was the answer to the nation's education problems.

He said he was not aware of any state schools that wanted to become charter schools but he imagined some might be attracted by the funding system for charter schools which was similar to a system that many schools adopted in the 1990s.

"When you look at the funding model, it's about funding in cash rather than staffing entitlement, it sort of harks back to days of bulk funding which some of us found relatively flexible and beneficial," he said.

Couillault said a key question for state schools converting to charter status would be whether local children would continue to have priority for enrolment.

"The devil will be in the detail of exactly what the expectation is of a state school that no doubt has a zone and an entitlement for local kids to go to it - what happens if they change to something that was special character?" he said.

But a Ministry of Education assessment of charter schools concluded there were major gaps in monitoring the schools and their evidence of how well their pupils were performing was not reliable.

It also said there was no evidence of innovative teaching practices beyond what could already be found in regular schools.

The OECD's recent economic survey of New Zealand said charter schools could help spread best practices and improve school governance.

But it said they might not add much to the existing system.

"The high autonomy of schools mean they can already tailor significantly their offer to local needs, suggesting partnerships schools would not add much in this domain. Similarly, designating these schools to take care of the learners whom the public system has not served well, risks stigmatising those learners and conveying the message that the public system is not able to address the needs of those learners with the greatest learning difficulties," it said.

"Experience from different countries indicates that the impact on equity and educational quality of publicly funding private providers is influenced by the institutional arrangements surrounding them. It is important regulation prevents undesirable outcomes for equity such as greater segregation through allowing the school to select students based on academic achievement or reduced professionalism by allowing unregistered teachers."

The Post Primary Teachers' Association had already scheduled paid union meetings before today's announcement was even known.

Speaking ahead of a meeting in Rotorua this afternoon PPTA Māori vice-president, Te Aomihia Taua-Glassie, said the union's members would not be happy, especially after the government cut $100 million from the free school lunch scheme.

"We are going to downgrade the food for our rangatahi, our tamariki, in order to pay for this vanity project, ideological obsession," she said.

Taua-Glassie said the union opposed the scheme because it privatised public education.